Supreme Court Ruling Casts Light on ‘Fair Use’

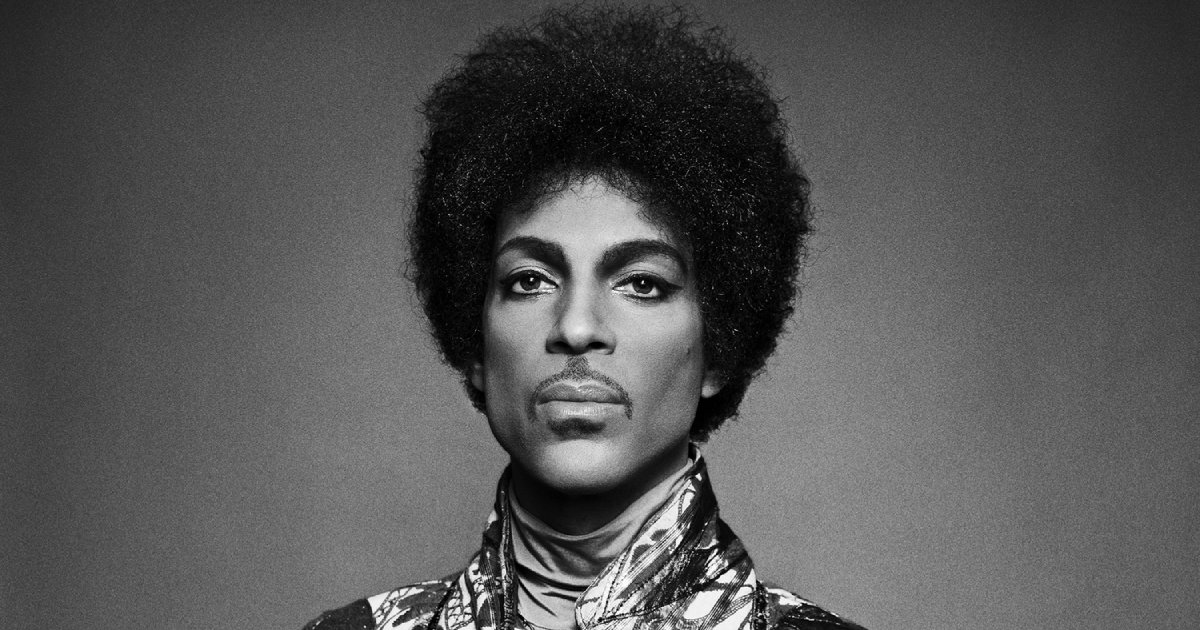

The U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling that an Andy Warhol image violated Lynn Goldsmith’s copyright on a photo of the late musician Prince will likely tighten the limits of fair use moving forward.

Fair use, which promotes freedom of expression in allowing the unlicensed use of copyright-protected works in certain circumstances, was at the heart of a lawsuit Goldsmith filed against the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts over the use of her 1981 photo of Prince. In 1984, Vanity Fair paid Goldsmith $400 to license the photo for a cover that Warhol created for the magazine. In 2016, Vanity Fair once again featured one of Warhol’s silkscreen portraits of Prince on its cover marking the musician’s death. This time, however, it paid the Warhol Foundation, not Goldsmith.

“I think it’s a significant contraction of where the court was,” said New York University law professor Amy Adler, who contributed to an amicus brief in support of the Warhol Foundation. “I think it is going to significantly limit the amount of borrowing and building on previous works that artists will engage in. The court seems less interested now in the artistic contribution of the second work and much more interested in commercial concerns.”

The Supreme Court voted 7-2 in favor of Goldsmith but seemed less focused on the creation of Warhol’s Prince series of silkscreens, which consisted of 16 pieces, than it was on the Warhol Foundation’s licensing of the work to Vanity Fair in 2016 (for which it was paid $10,000). In issuing the ruling, the Court didn’t establish “bright line” rules, but provided “clarity” into derivative works and signaled that “not all appropriations” will be determined to be fair use, said Alex Malbin, an attorney at Ferdinand IP Law Group.

“This case was much more business-focused, and the court only looked at whether there was a commercial purpose for the licensing,” said Jed Ferdinand, Managing Director at Ferdinand IP Law Group. “There was a clear commercial purpose for the Warhol work, and this is no longer fair use, and the court got it right.”

The case wended its way through federal and appellate courts, which issued conflicting decisions before the case moved to the Supreme Court. At the Federal District Court in Manhattan, Judge John Koeltl ruled that Warhol had created something new by giving the photograph new meaning. But the U.S. Appeals Court for the Second Circuit said judges should compare how similar two works are and leave the interpretation for others.

“The district judge should not assume the role of art critic and seek to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue,” Judge Gerard Lynch wrote for the panel. “That is so both because judges are typically unsuited to make aesthetic judgments and because such perceptions are inherently subjective.”

In writing for the majority, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor sided with Lynch and Goldsmith in arguing that the “critical factor” in fair use analysis is the “purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes.”