Do Licensed Goods Fit in the Secondhand Market?

Amid a surge in popularity of secondhand goods, the question remains whether licensing can cash in on this growing business.

For the most part, it doesn’t look likely. Under the Lanham Act’s first sale doctrine, trademarked products can be resold without risk of infringement. But while trademarked products can’t benefit financially from the growing resale business—unlike NFTs, where royalties are paid on secondary sales—there is the benefit of raising a brand’s profile. This is especially true given that resale, especially in apparel, plays well with companies’ sustainability goals and the focus on a circular economy.

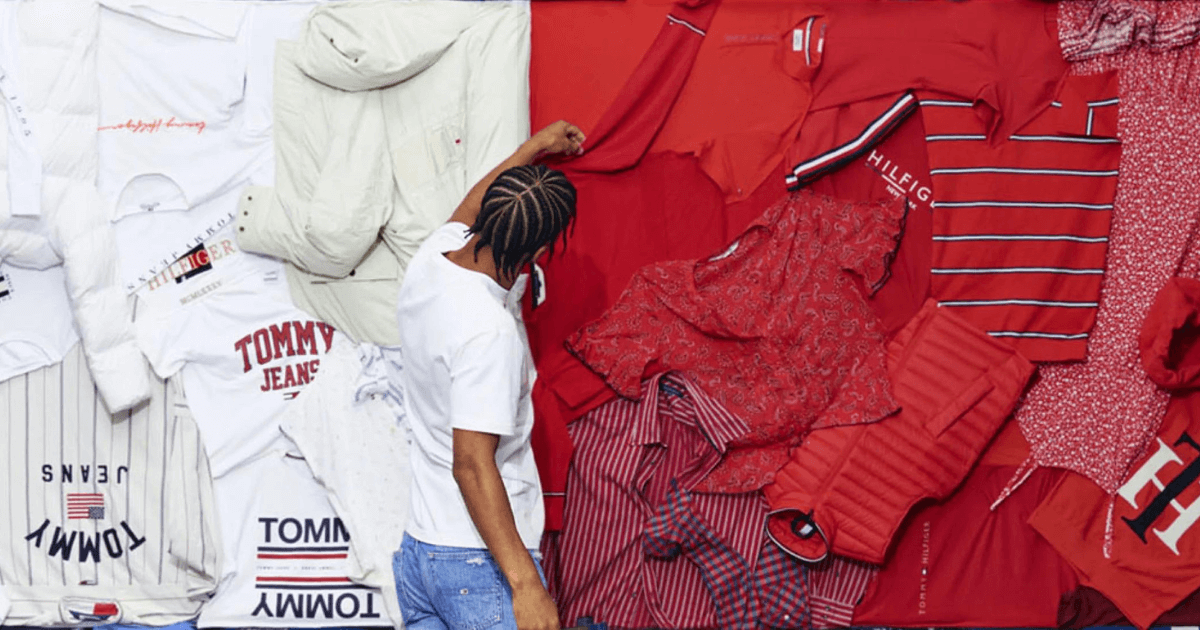

For example, fashion resale company ThredUp—which targets Gen Z consumers—expects to provide its “Resale as a Service” platform to more than 40 brands by year end. PVH Corp.’s Tommy Hilfiger label is a recent addition. Under the deal, U.S. customers can generate a prepaid label, fill a box or bag with clothing (in the case of Tommy Hilfiger, with men’s apparel) and ship it to ThredUp for free. For the apparel that can be resold, consumers receive a Tommy Hilfiger shopping credit.

“The U.S, market is packed with circular potential and we’re hoping to make a long-lasting difference,” said Esther Verburg, global EVP for sustainable business and innovation at Tommy Hilfiger.

That long-lasting difference can be lucrative both for resale platforms and the brands they work with. The resale business is forecast to be an $82-billion global market by 2026, up from $41 billion this year and from $20 billion in 2017. In fact, Wells Fargo analysts have said platform agreements pairing brands with the likes of ThredUp, RealReal, Vestiaire, and others are potentially more lucrative than the consumer business. And licensors may not receive monetary benefits on the secondary market, their brands are certainly in evidence. For example, The Gucci paired with Micket Mouse on sneakers and a crossbody bag were available on RealReal priced at $825 and $1,325, respectively. At the lower end, a University of Richmond baseball cap was available on ThredUp at $11.99.\

Yet resale can be a vexing issue for luxury brands. Secondhand luxury isn’t new, but recent price increases by some of the labels have driven many buyers to seek less expensive items on the secondary market. Used luxury sales were up 65% last year compared to 2017, while those of new goods increased 12%, according to Bain & Co. Those secondhand sales are expected to increase 15% annually during the next five years.

As a result, the secondhand market has divided luxury with some brands—including Gucci maker Kernig, Burberry Group, and Stella McCartney—supporting the practice while others like Channel and Hermes don’t participate due, in part, to the potential for cannibalizing sales of higher priced goods. Some brands like Rolex have addressed secondary markets by selling limited edition watches.

“I have not seen concerns specifically expressed in licensing agreements because the manufacturer/distributor is limited in how they can control the market,” said Jed Ferdinand, founder of the Ferdinand IP Law Group. “Licensors will try to strictly limit product distribution channels and territories, especially for luxury items. You will definitely see a provision where the licensee cannot knowingly sell the licensed products to a customer that will sell the product outside of the permitted territory or distribution channel. But since there is typically a ‘knowingly’ standard, even that does not have much teeth to it.”

Yet in the current landscape, where inflation and price increases are taking a toll on business, even the resale market isn’t immune. The discount segment of Teacup’s business fell 7% in the second quarter, said CEO James Reinhart. And the average order value at RealReal dropped to $485-$490 from $520 at the end of June, Co-CEO and CFO Robert Julian said.

“There’s been a shift from higher-priced items, like fine jewelry and watches, to lower-priced items like ready-to-wear apparel and shoes,” RealReal Co-CEO Rati Levesque said. And while Levesque said the company expects demand to normalize to pre-pandemic levels across categories at some point, this shift to lower-priced items occurred more quickly than anticipated.